Steve K

Flashlight Enthusiast

I just completed work on a Supernova Triple headlight, and thought the CPF crowd (or at least this little corner of CPF) might find it interesting. I've got a number of photos and am working on writing up the story of what happened. Here's Chapter 1 for your entertainment.

chapter 1. disassembly

a fellow on a bike forum asked for help with a Supernova Triple

dynamo light. I'd been curious about these lights, so I offered to try

to fix it if he would cover the cost of the parts and the shipping. He

had gotten the light for free (someone else had damaged it), so he

agreed. My assumption was that the failure was probably a broken

wire or some other obvious damage, so it shouldn't be too hard to

repair. I did mention to the owner that it could be damage that just

couldn't be repaired by anyone but the factory, though.

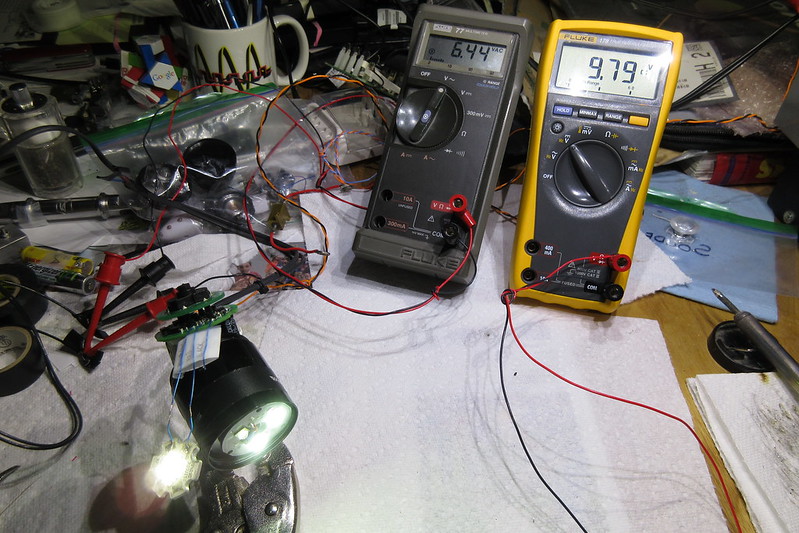

I've finished working on the light and thought that this group might

enjoy seeing how the light is built and some of the troubleshooting

and repair(?) process. For the sake of drama and interest, I don't

want to tell you how the story ends, but would prefer to let the story

unfold.

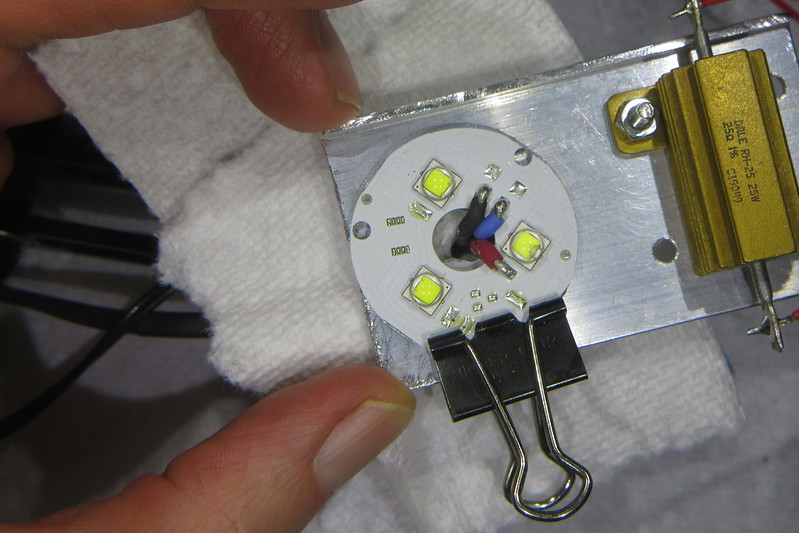

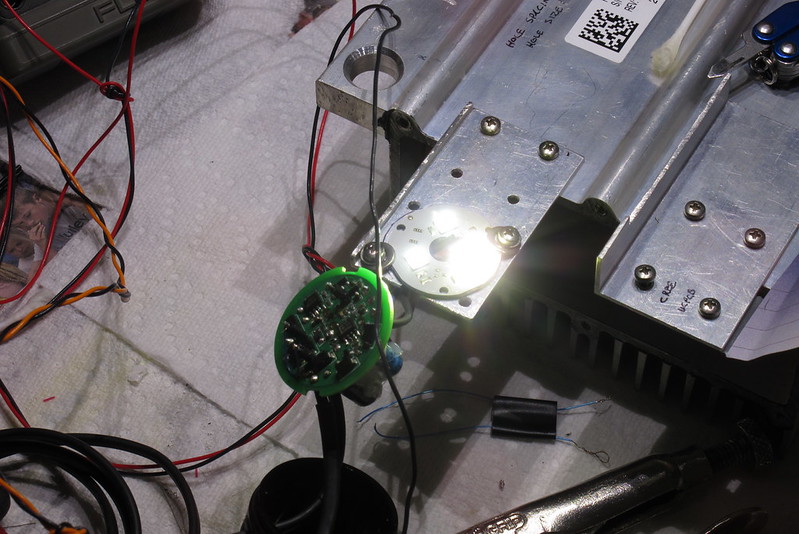

The light is housed in a very nice aluminum body with a bracket of

similar quality. Even if all of the electronics was dead, it would

make a nice host for a design of one's own.

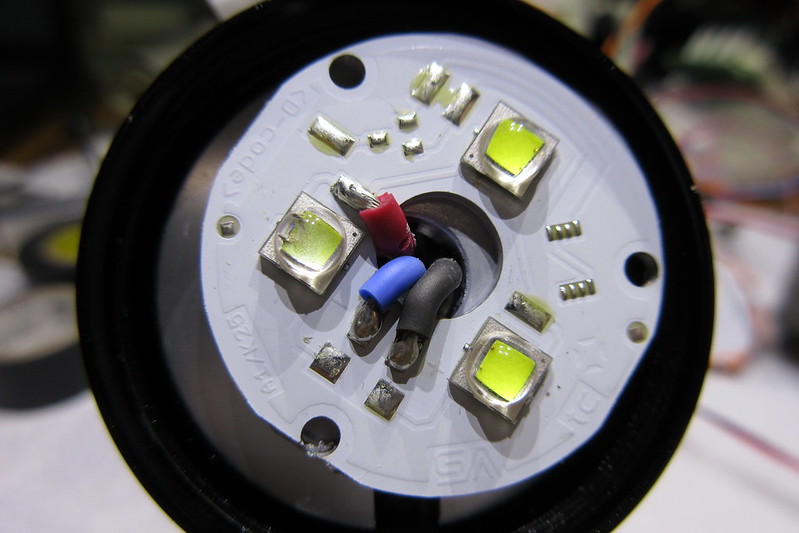

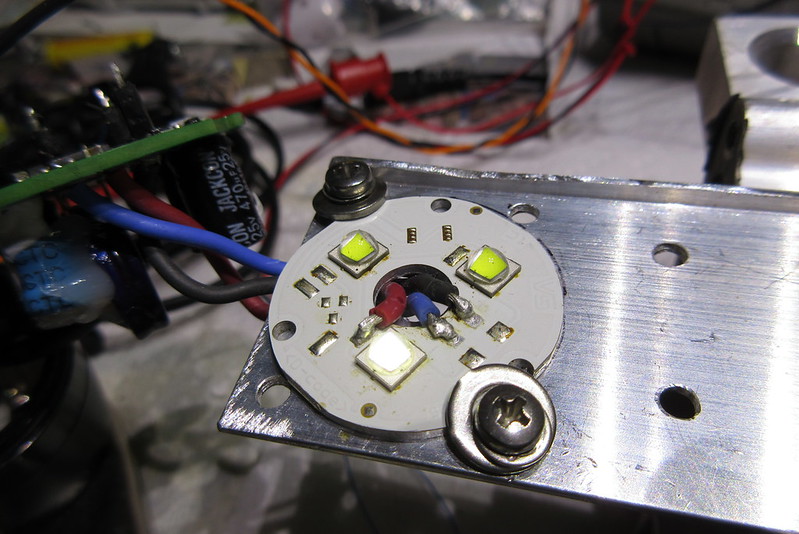

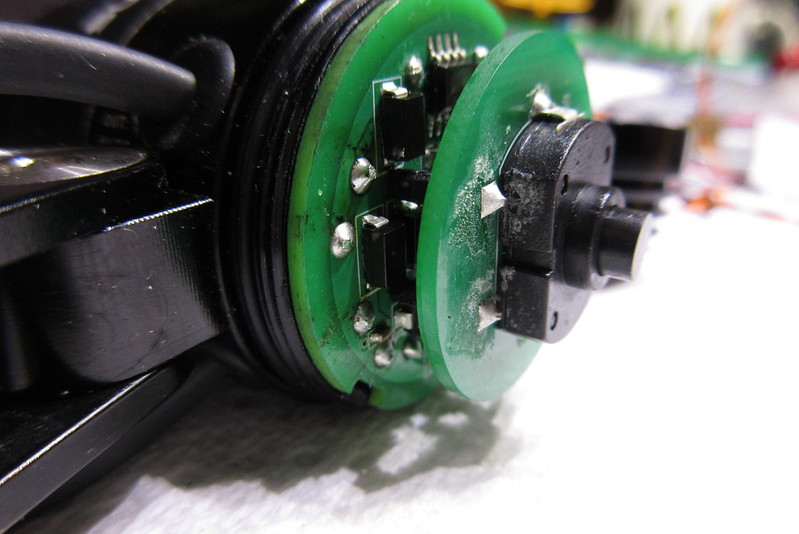

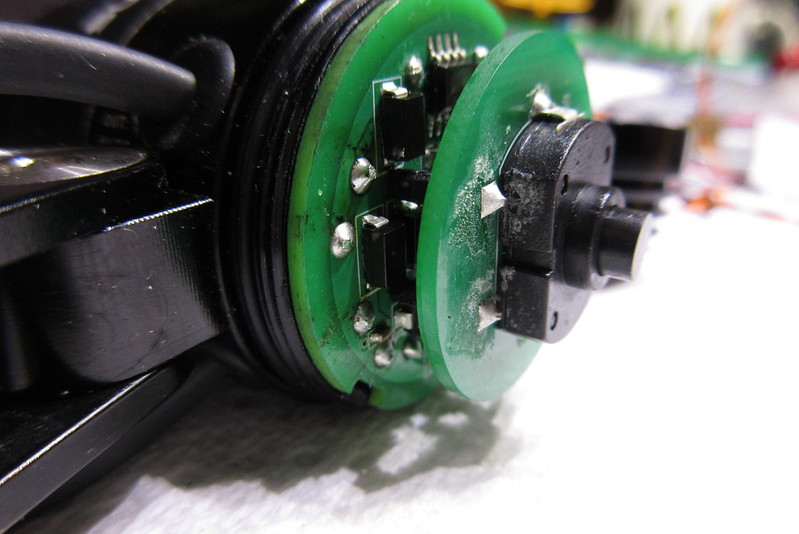

The light has a front bezel that unscrews, revealing the triple optics

and the LED MCPCB (Metal Core Printed Circuit Board). At the

rear of the light is a screw-on cap, which has a boot for the push

switch, and which covers the circuit boards.

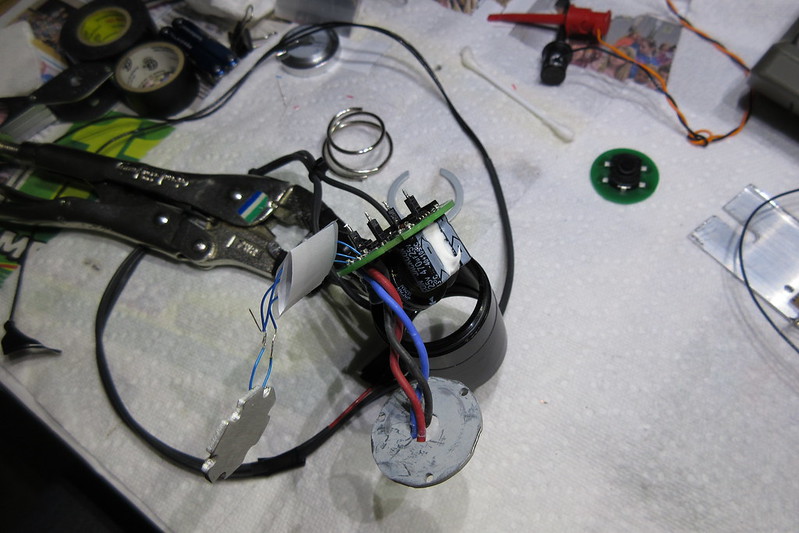

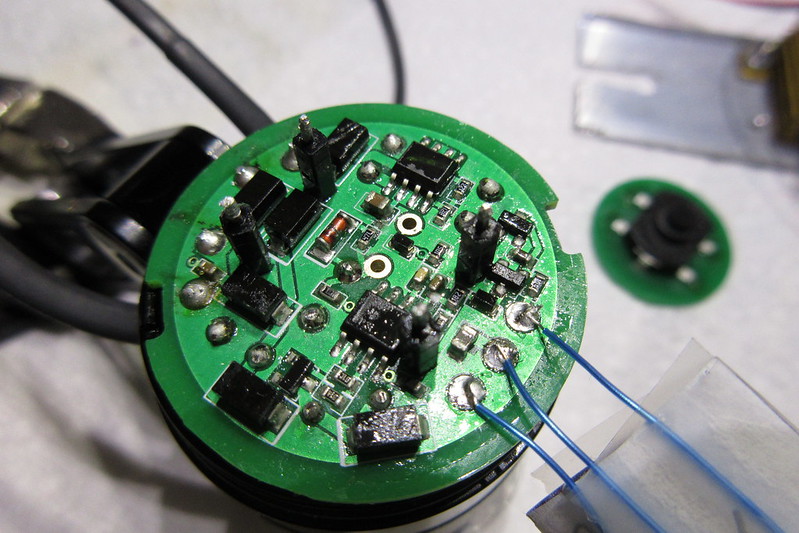

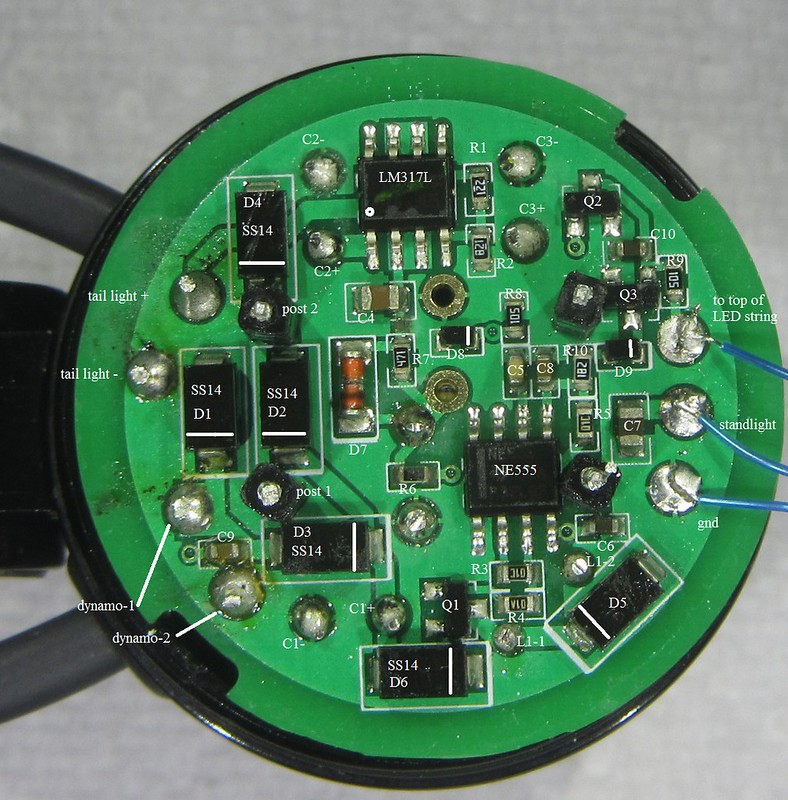

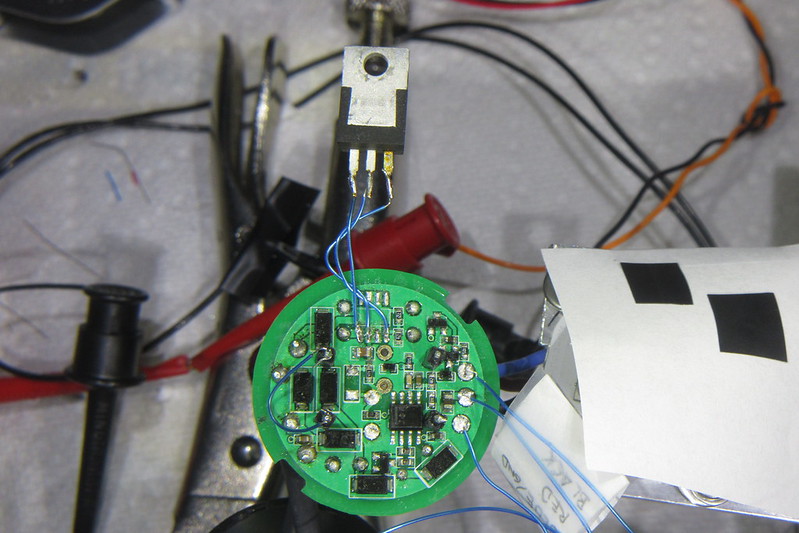

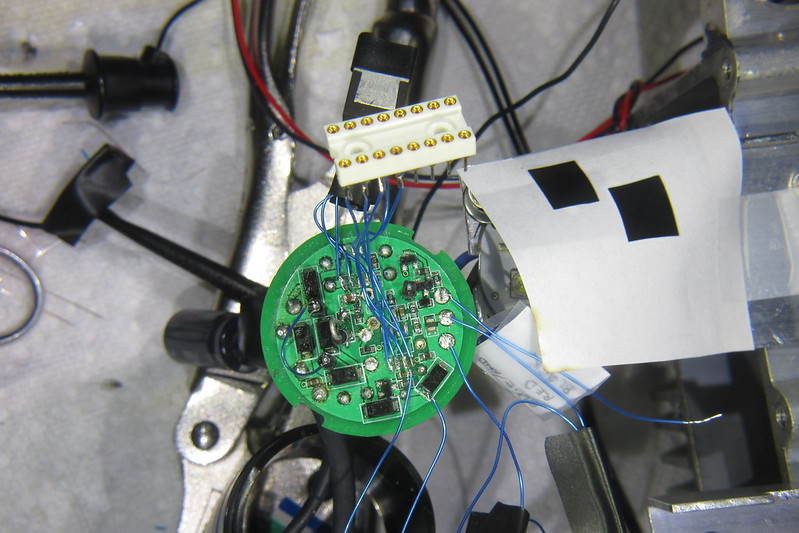

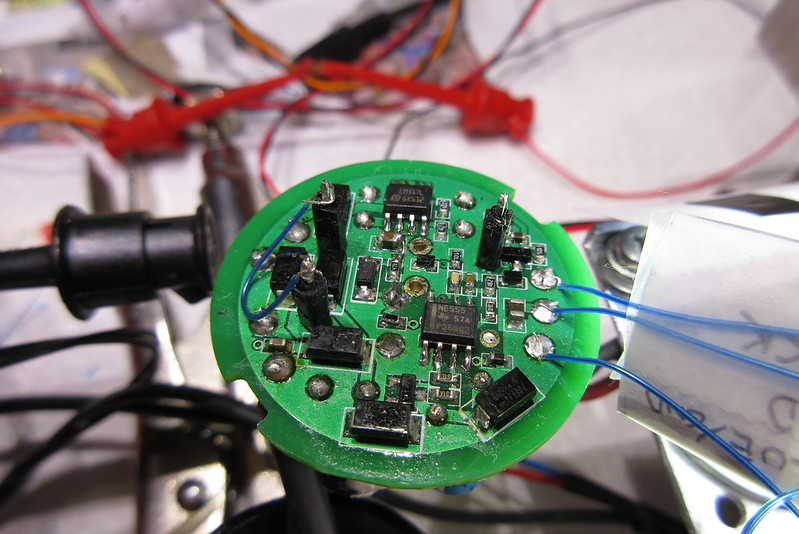

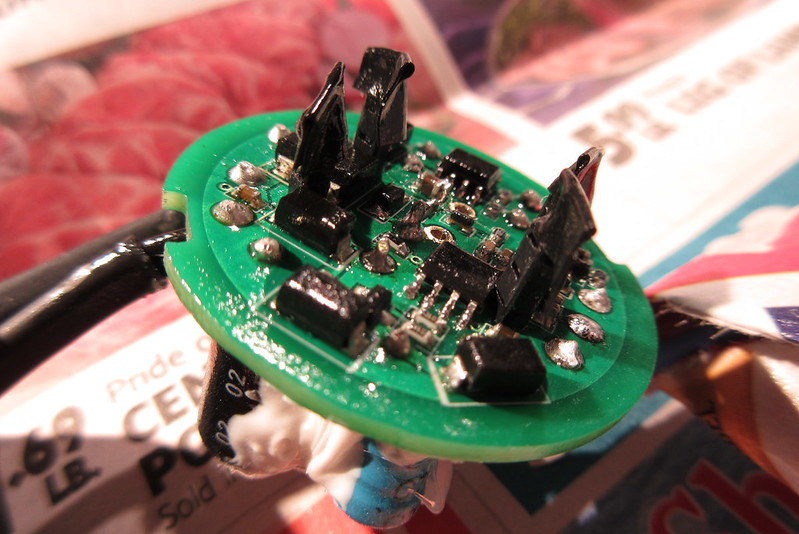

There are two circuit boards. The small board has just one

component.... the push switch. The large board has the rest of the

components. The boards are both built well... fairly thick, to

handle the force of actuating the push switch.

The lower board has conformal coating to resist moisture. Overall, they looked like they

were high quality, which matches the rest of the light.

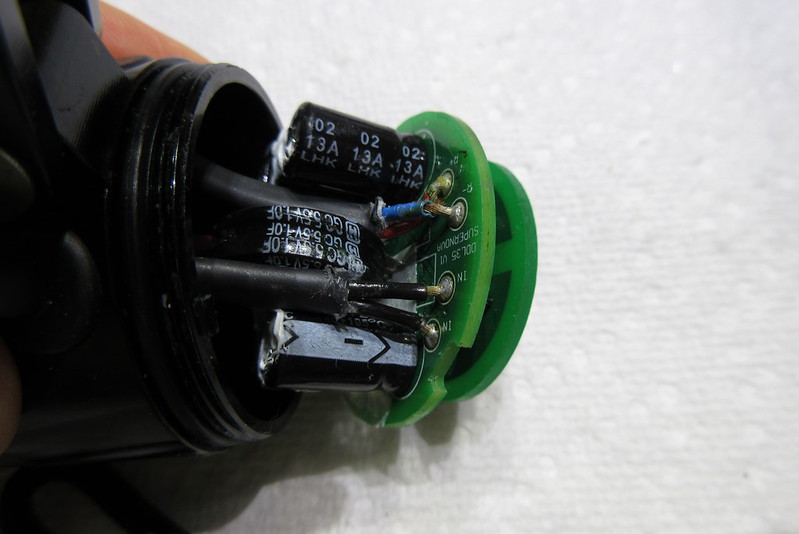

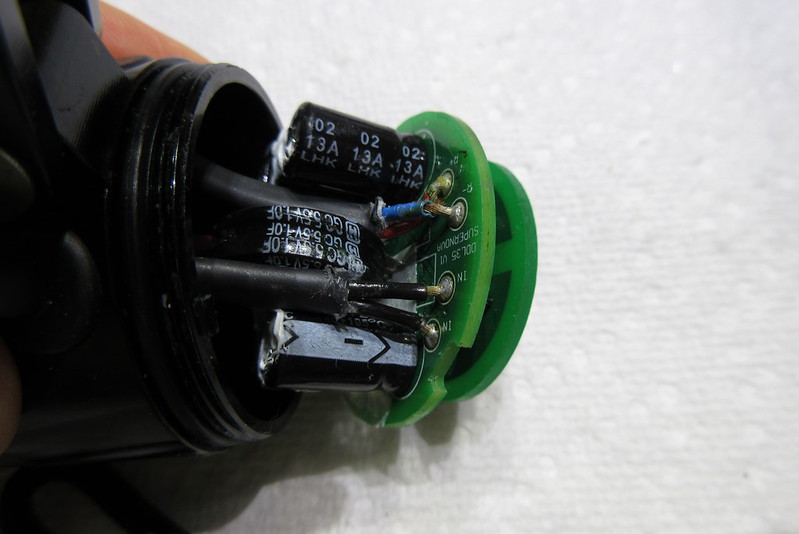

It took a bit of head scratching before I figured out how to get

access to the bottom of the lower circuit board. There is one wire

pair that goes to the dynamo, and one wire pair that goes to the

taillight. By sliding these wires through their grommets and into the

housing, there was enough slack in the wires to slide the circuit

board partly out of the housing. The board was still restrained by

the three wires going to the LED MCPCB.

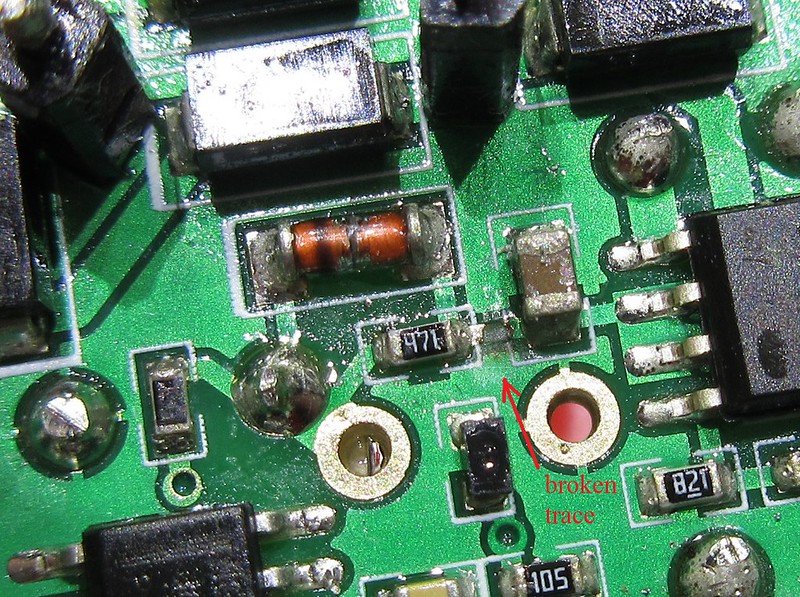

My hopes of finding a simple broken wire were ruined, so now I

had to actually do some work and figure out what was wrong with

the light.

.... to be continued.... (in next post)

chapter 1. disassembly

a fellow on a bike forum asked for help with a Supernova Triple

dynamo light. I'd been curious about these lights, so I offered to try

to fix it if he would cover the cost of the parts and the shipping. He

had gotten the light for free (someone else had damaged it), so he

agreed. My assumption was that the failure was probably a broken

wire or some other obvious damage, so it shouldn't be too hard to

repair. I did mention to the owner that it could be damage that just

couldn't be repaired by anyone but the factory, though.

I've finished working on the light and thought that this group might

enjoy seeing how the light is built and some of the troubleshooting

and repair(?) process. For the sake of drama and interest, I don't

want to tell you how the story ends, but would prefer to let the story

unfold.

The light is housed in a very nice aluminum body with a bracket of

similar quality. Even if all of the electronics was dead, it would

make a nice host for a design of one's own.

The light has a front bezel that unscrews, revealing the triple optics

and the LED MCPCB (Metal Core Printed Circuit Board). At the

rear of the light is a screw-on cap, which has a boot for the push

switch, and which covers the circuit boards.

There are two circuit boards. The small board has just one

component.... the push switch. The large board has the rest of the

components. The boards are both built well... fairly thick, to

handle the force of actuating the push switch.

The lower board has conformal coating to resist moisture. Overall, they looked like they

were high quality, which matches the rest of the light.

It took a bit of head scratching before I figured out how to get

access to the bottom of the lower circuit board. There is one wire

pair that goes to the dynamo, and one wire pair that goes to the

taillight. By sliding these wires through their grommets and into the

housing, there was enough slack in the wires to slide the circuit

board partly out of the housing. The board was still restrained by

the three wires going to the LED MCPCB.

My hopes of finding a simple broken wire were ruined, so now I

had to actually do some work and figure out what was wrong with

the light.

.... to be continued.... (in next post)